|

|

|

|

|

|

SUBSCRIBER EXCLUSIVE | SEPTEMBER 01, 2023 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Did you miss our previous newsletter? You may find it here. |

|

|

|

Missing The Event, Finding The Story |

|

|

John Haughey |

|

Hurricane Idalia materialized as a radar smudge off the Yucatan on Saturday, metastasized into a tropical storm on Sunday, and then morphed into Monday’s headline news where it would remain for the next 96 hours, from its mushrooming, menacing approach to its dissipation in the Carolinas, in the end a lot of rain and a name to be etched—but not “retired’—in the annuals of hurricanes.

As Idalia blew-up on its bullet-train track north Monday, decisions were being made by residents, businesses, and governments from Key West, Florida, to Wilmington, North Carolina, in reaction to the National Hurricane Center’s (NHC) four daily updates, each recalibrating projected wind speeds, storm surges, and the spaghetti splays of possible landfalls and subsequent potential marches across four states.

The NHC bulletins kickstarted a topical flood zone of renewed speculation by roundtables of TV talking heads, spurred frantic local news scenes of businesses boarding up, shoppers stocking up, drivers gassing up, and press conferences led by governors of states in Idalia’s projected path updating evacuation orders, shelter openings, emergency responders activations, in-bound utility linemen, and ceaseless pleas for those in low-lying coastal areas to seek higher ground.

With the Sunshine State being Ground Zero in Idalia’s path, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis suspended his Republican presidential campaign and got plenty of national TV air time to demonstrate his crisis management skills to voters in Iowa. Geography and the mercurial nature of hurricanes have advantages.

Those 36 hours before Idalia’s 8 a.m. Aug. 30 landfall on Keaton Beach in Florida’s Big Bend also fostered a blur of sudden decisions by media organizations, such as The Epoch Times and EpochTV, in responding to an unfolding event that was building into an emergency.

The question: Where to go? Where to go to cover the landfall, to be as close as possible to the landfall, to see it, feel it, share it with readers and viewers across the nation, across the world. |

|

|

The intersection of Cross and Athens streets off Dodecanese Boulevard in Tarpon Springs, Fla., was still flooded around noon on Aug. 29, 2023, more than 12 hours after Hurricane Idalia churned past 125 miles to the west the night before. (John Haughey/The Epoch Times) |

|

The Plan or Something Like That

Through Monday, tracks projected landfalls near Homosassa and Crystal River, about 80-to-100 miles north of Tampa Bay, with storm surges of up to 12 feet in the swampy Nature Coast and of at least 4-to-8 feet in Tampa Bay, already plagued by tidal “day flooding.”

And so, also in that Monday-to-midday-Tuesday window, editors, reporters, and television camera crews were making decisions, gearing up, securing flights, renting cars, preparing to cover the hurricane crashing ashore.

To boost The Epoch Times’ Florida staff spearheaded by Nanette Holt with T.J. Muscaro in the Tampa Bay area and Samantha Flom in Jacksonville—a team that would go on to document Idalia’s cross-state romp—EpochTV videographer Shenghua Sung was dispatched from New York.

I was to join Shenghua from my home in Lakeland, 35 miles east of Tampa, and we were to go where the action was. Or something like that. There were some logistical challenges with this plan. Namely, Shenghua flew into Orlando, arriving Tuesday evening, and when he contacted me that night, he was already in Tampa Bay, already headed out to St. Petersburg and Clearwater, where Idalia was churning 125 miles off the beaches.

By now, of course, Idalia’s projected track had been steadily ticking north, into the Big Bend area. It was apparent by late Tuesday, early Wednesday, that Tallahassee would have been the place to launch a landfall foray.

And that was fine with me. I know this about hurricane coverage: There is the event and then there is the story. You can miss the event, but you can tell the story. |

|

Was this forwarded to you? |

|

|

|

|

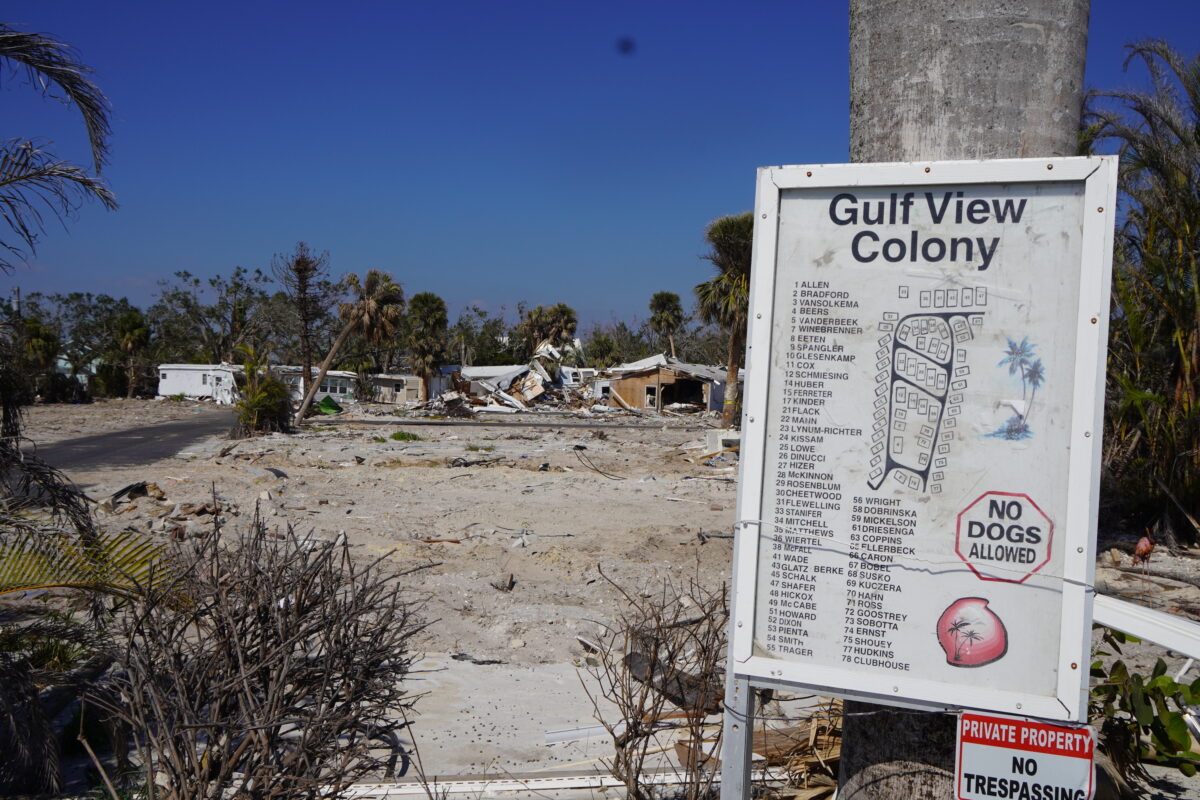

All that remains of the 78-lot Gulf View Colony mobile home park off Estero Boulevard in Ft. Myers Beach, Fla., is rubble, clawed earth, and this directory of neighbors who are neighbors no more, five months after Hurricane Ian swamped Estero Island in an 18-foot storm surge. (John Haughey/The Epoch Times) |

|

Of Storm-Chasers And Story-Tellers

I know after the breathless excitement of the event—the tracking of a named storm’s lifespan, from radar blip to Jim Cantore on a beach—the real story begins, a story of many stories, for each hurricane leaves behind a mosaic of challenges that live on in their memory for years across a wide swath of communities, cities, and counties.

One begins and ends in a span of days; the other becomes the fiber of day-to-day affairs for years. Sometimes, for decades. Sometimes, forever. As a reporter for The Charlotte Sun on Friday, Aug. 13, 2004, I learned the difference between event coverage and reporting the story when Hurricane Charley unexpectedly stormed into Charlotte Harbor, exploding into a Category 4 bomb, flattening everything within its 10-mile eye-wall, before storming up the Peace River like a banshee on meth to wreak havoc across Central Florida.

Charley is an outlier among the nastiest of the nasty “retired” hurricanes; known more for its wicked winds than the water it pushed ashore in its rocket run across the state and into the Atlantic, where it bounced back to throw a few more punches in the Carolinas.

As a county government reporter, Charley was to be thematic in nearly every article I wrote for the next six years. Its aftermath remains a story, the story, there two decades later—it’s why the Tampa Bay Rays now have spring training in Murdock, why Punta Gorda looks so new, and why there are now three Captiva islands where there were two.

The recovery story is often grueling at first—the heat and constant rains in places without power and blue-tarped roofs, the clearing of debris, indigent workers living in the woods, the race against mold making untouched homes uninhabitable, the buzz of generators in the dark nights, curfews enforced by patrolling National Guard troops tossing MREs to those figuring out how to get along in the rubble.

Then the recovery story gets less sexy and more mundane, the narrative carried forward day-to-day, the part of the story where FEMA is, where insurance disputes are, and where local governments will be for years to come.

The story of Hurricane Ian’s Category 5 romp through Southwest Florida in September 2022 was not its awesome, fearful landfall, albeit as vivid an event as a camera could love, but in its aftermath, making it as much of a story today as it was 11 months ago.

But in nevertheless attempting to get to its Ft. Myers Beach landfall with videographer Jack Pagano, we got as far south as a dairy where drowned cows lay along its fence lines. This was the story there. We told that story.

I would go to Ft. Myers Beach five months later and find the story in rubble-lined streets, intermittent power, and neighborhoods of broken, busted homes. That is the story there. That remains the story there. |

|

|

More than 14 hours after Hurricane Idalia passed west of Homosassa, Florida, this Los Angeles, California-based Australian Broadcast Co. news team was telling the story on Aug. 30 of the flooded Homosassa River, more than 120 miles south of where the storm made its landfall. (John Haughey/The Epoch Times) |

|

The Stories of The Stories

And so, Shenghua and I ended up taking U.S. 19 north from Clearwater to Tarpon Springs, where businesses along Dodecanese Street—on the Sponge Docks, a tourist attraction and commercial fishing port—were scrambling to sweep saltwater from their stores back into the Anclote River, back into the sea.

It wasn’t the crash-and-boom of the landfall 12 hours earlier and 185 miles north—Idalia’s disintegrating eye wall carrying the nation’s eyeballs with it across Georgia and into the Carolinas—but storm surge flooding was the story across the Tampa Bay Area. It certainly was the story in Tarpon Springs.

Further north on U.S. 19, the storm-swollen Homosassa River was rising and with the mid-afternoon high tide, aptly named Fishbowl Drive near Homosassa Springs was a lake. People who had evacuated for the event and returned home afterward, were now isolated as the rising river swallowed bridges down the road.

This was the story in Homosassa.

Idalia won’t be the last storm to menace a coast within the United States before the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season concludes in November. In fact, the “mean season” has just begun.

There will be, again, that crucial window where decisions are made with dart boards: Go here or go there? There will be, again, the frantic rush of moment-to-moment updates, the forecasts, the punditry, the excitement of it all, the storm-chasers seeking the event.

And then there will be the story, the story of many stories. Long after the seminal event is a footnote, its enduring footprint of reshaped landscapes, upended lives, and altered history will be the story, the story of many stories, the little stories that are not merely "part" of the big picture, they are the big picture—each and every one of them. |

|

|

|

|

John Haughey |

|

|

|

Thank you for being a subscriber |

|

|

|

Copyright © 2023 The Epoch Times. All rights reserved. |